No. 3: The ministry of imagination

Dear Friends,

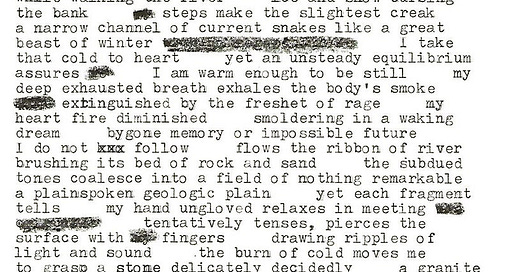

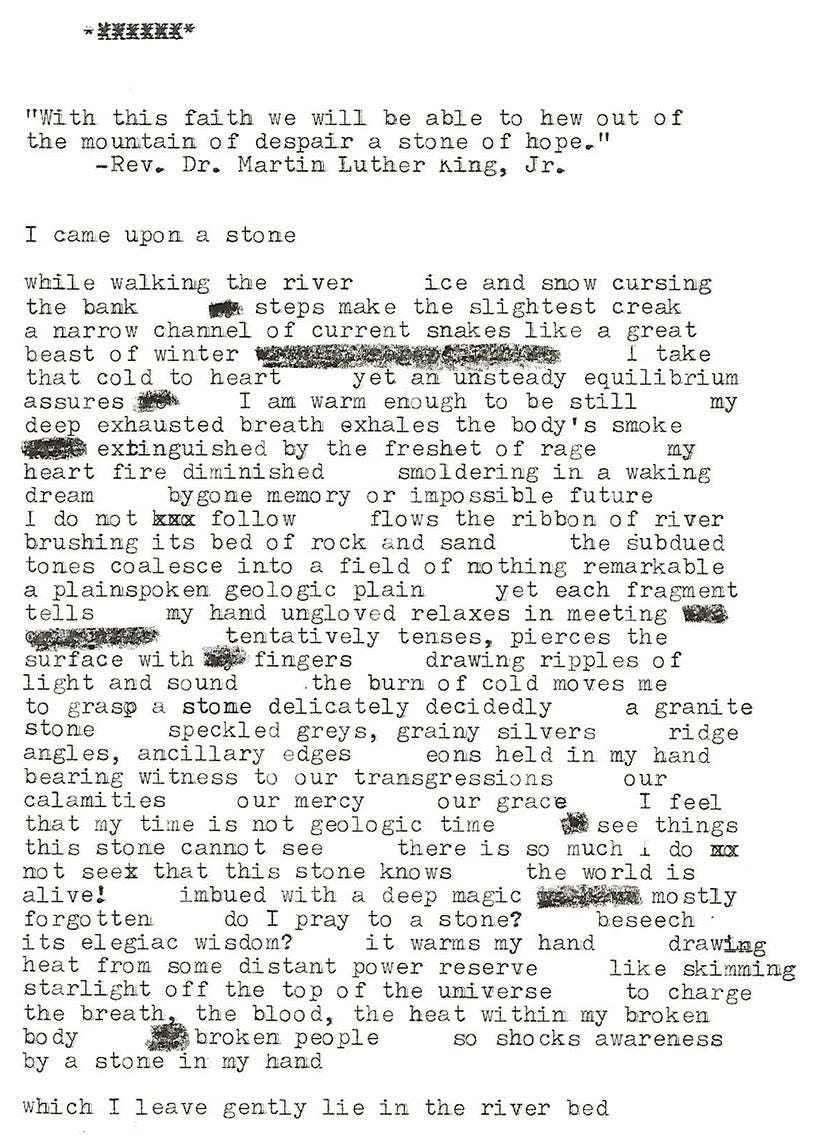

I’ve been working on a poem over the past week. As a new poem with only a handful of revisions behind it, I make no claims about its state of completion. Experimenting with different processes always leads to unexpected outcomes, though. In this case: first handwritten in pencil in my sketchbook (analog), then transcribed into the computer followed by a few rounds of revisions (digital), then typed out with the typewriter with some minor revisions (analog), then edited again by blacking out some clunkers (analog). It’s done enough and good enough to share.

Martin Luther King, Jr. has been on my mind, even before the annual call to remember his life and work that is marked by the holiday on the third Monday of January each year. He exists in a context, in a continuum of the struggle for justice that spans centuries and continues today. The civil rights movement of his time had many leaders and thousands of activists and organizers who put their bodies on the line to engage in this struggle. We are called to remember Dr. King’s words and actions, which still speak so directly and powerfully to this current moment, inspiring present-day movements for collective liberation, inspiring me on my journey of learning about how to move from being comfortably not racist to staunchly anti-racist. I’m a work in progress.

The epigraph that opens the poem is from Dr. King’s “I have a dream” speech, delivered from the Lincoln Memorial on August 28, 1963 at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, D.C. I wonder, when, if ever, was the last time you watched (or listened to) Dr. King’s speech? I confess that I had not watched the entire speech until a few months ago. In the darkness and despair of this past week, I watched it again, and I found hope, historical perspective, and collective power reaching out from the grainy images and scratchy audio recorded nearly 60 years ago. I think you should watch it, too. Because what Dr. King did in his sermon on that sweltering summer day in front of several hundred thousand people is exclaim a poetic prophecy, a vision of a different world: that is, a United States of America not plagued by racial segregation and economic inequity. In 1963 under Jim Crow laws, that vision of racial integration was as unimaginable to segregationists then as police and prison abolition may seem to many of us today. Consider how much of what was imagined by the civil rights movement has materialized, and how much more has yet to be realized.

Last week in her sermon (via Zoom, of course), Rev. Joan Javier-Duval of the Unitarian Church of Montpelier also ruminated on the power of imagination to “conjure up and propos[e] alternative futures to any single one desperately forced upon us by power hoarding leaders.” Her message referenced and built on the work of progressive Christian theologian Walter Brueggemann, whose study of biblical Old Testament prophets (Moses, in particular) in The Prophetic Imagination articulates the essential role of the prophet to imagine new futures through poetic language:

The prophet does not ask if the vision can be implemented, for questions of implementation are of no consequence until the vision can be imagined. The imagination must come before the implementation. Our culture is competent to implement almost anything and to imagine almost nothing. The same royal consciousness that makes it possible to implement anything and everything is the one that shrinks imagination because imagination is a danger. Thus every totalitarian regime is frightened of the artist. It is the vocation of the prophet to keep alive the ministry of imagination, to keep on conjuring and proposing futures alternative to the single one the king wants to urge as the only thinkable one.

I am so enthralled by the phrase “ministry of imagination”! – although my interpretation of “ministry” is not as a religious activity but as a governmental department or institution. As in: the Ministry of Magic. As in: Harry Potter. I’ve been reading the series aloud to my kids almost daily for weeks, so our world is inflected with Potter references, and, upon first hearing the phrase in the Brueggeman quote from Rev. Joan, I was certain she was speaking about a Ministry of Imagination, some mythical institution devoted to imagining alternative futures. The ministers in residence there are prophets, poets, artists, dreamers, seers, visionaries, futurists, crackpot inventors, speculative designers, and, most importantly, young children, who remain our best visionaries. Their purpose, as it has always been, is to flood the world with countless alternative visions for how we might live in collective liberation, justice, and compassion with each other and with the natural world. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. would, of course, be an honorary founding member, posthumous, of the Ministry of Imagination.

More radical imagination from the American Latino poet, Martín Espada, who writes in “Imagine the Angels of Bread” (1996):

This is the year that squatters evict landlords,

gazing like admirals from the rail

of the roofdeck

or levitating hands in praise

of steam in the shower;

this is the year

that shawled refugees deport judges,

who stare at the floor

and their swollen feet

as files are stamped

with their destination;

this is the year that police revolvers,

stove-hot, blister the fingers

of raging cops,

and nightsticks splinter

in their palms;

this is the year

that dark-skinned men

lynched a century ago

return to sip coffee quietly

with the apologizing descendants

of their executioners.

[...]

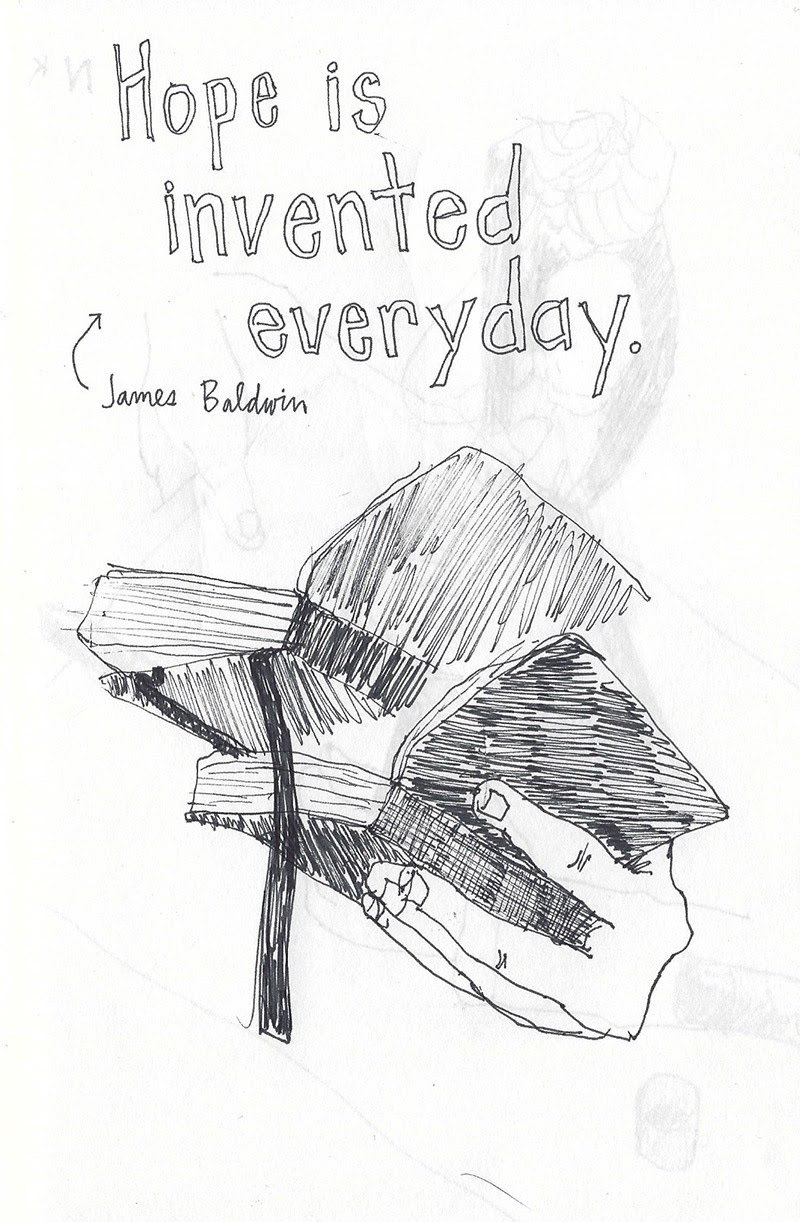

I’ll end with James Baldwin responding, when asked “What, then, about hope?”:

As always, thank you for reading and responding. Here’s to inventing hope daily.

Peace and love,

Jeremy

PS: I’m grateful to the facilitators of the Beloved Conversations: Virtual program for creating a structured curriculum and discussion-based program focusing on racial justice, which (re)introduced me to many excellent resources, including the Martín Espada poem and Dr. King’s work, life, and significance.